Under the Hood: How PyTorch Chooses Attention Kernels and Why It Matters for Performance

A deep dive into PyTorch’s attention kernel selection and what each choice means for your transformer models

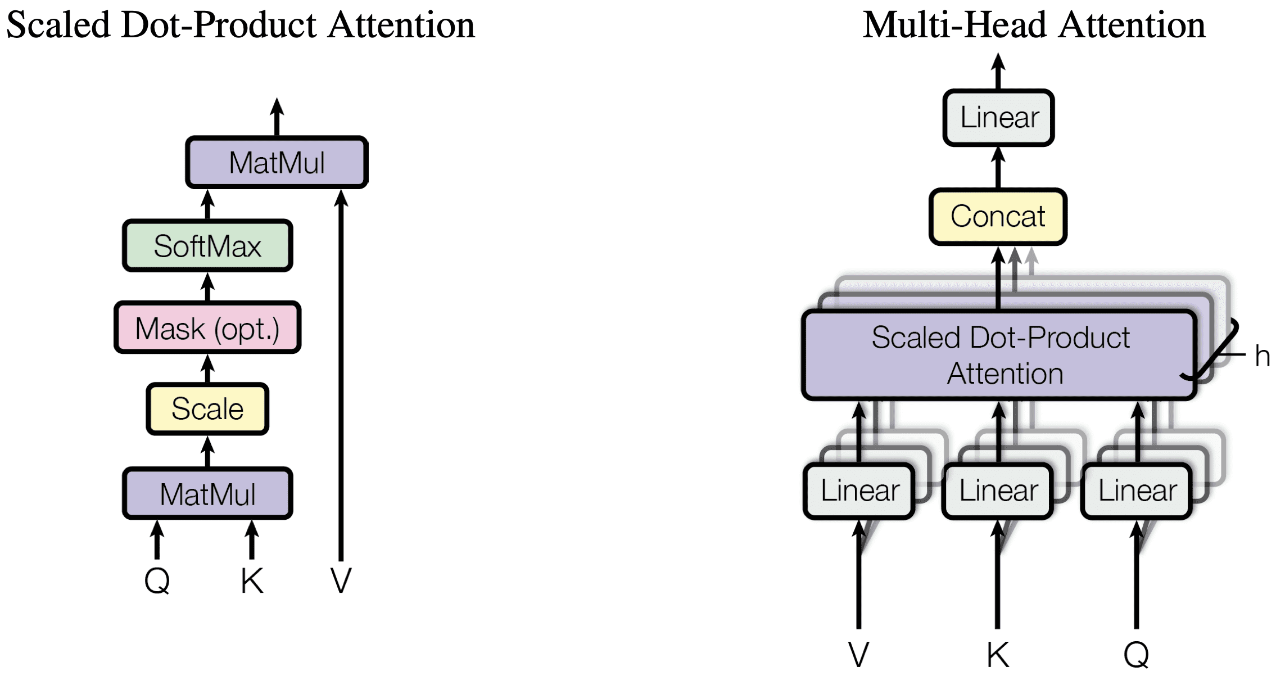

If you’ve ever wondered why your transformer model sometimes runs faster or slower without any obvious changes to your code, the answer might lie in PyTorch’s attention kernel selection. PyTorch’s scaled_dot_product_attention function doesn’t just implement attention — it intelligently chooses between different optimized kernels based on your configuration.

Today, we’re going to peek under the hood and see exactly which kernels PyTorch uses, how they perform, and when you should care about each one.

The Secret Configuration That Changes Everything

PyTorch gives you control over which attention implementation to use through a seemingly simple function:

1

2

3

4

5

torch.backends.cuda.sdp_kernel(

enable_flash=...,

enable_math=...,

enable_mem_efficient=...

)

But what actually happens when you flip these switches? Let’s find out through systematic profiling.

The Experiment: Profiling Real Attention Kernels

To understand what’s really happening, I set up a controlled experiment using realistic transformer dimensions:

Test Setup:

- Input tensors:

[2, 8, 512, 64](batch=2, heads=8, seq_len=512, head_dim=64) - Data type: FP16 (optimal for Tensor Core utilization)

- Hardware: NVIDIA RTX A6000 (GA102, SM86, 84 SMs, 48GB GDDR6)

- Memory bandwidth: 768 GB/s theoretical, ~650 GB/s achievable

- L2 Cache: 6MB shared across all SMs

- Shared memory per SM: 100KB (99KB usable)

- Profiling method: PyTorch profiler + CUDA Events for microsecond precision

- Iterations: 5 runs per configuration with GPU warm-up

Why these dimensions matter: 512×64 attention matrices fit comfortably in shared memory (256KB for Q, K, V combined), allowing us to see pure computational differences rather than memory-bound behavior.

Configuration 1: The Surprising Winner

All Flags Disabled → CUDNN Takes Over

1

2

3

4

5

torch.backends.cuda.sdp_kernel(

enable_flash=False,

enable_math=False,

enable_mem_efficient=False

)

What actually runs:

1

cudnn_generated_fort_native_sdpa_sm80_flash_fprop_wmma_f16_knob_6_128x64x64_4x1x1_kernel0_0

Wait, that kernel name contains “flash” even though FlashAttention is disabled? Here’s the plot twist: when you disable all PyTorch-specific options, PyTorch falls back to CUDNN’s own optimized attention implementation — and it’s surprisingly good.

Performance Results:

- Execution time: 16.26μs per call

- Memory footprint: 40KB shared memory (40% of available)

- Grid config: [4, 8, 2] = 64 thread blocks

- Block config: [128, 1, 1] = 4 warps per block

- Occupancy: ~75% theoretical (limited by shared memory)

- Tensor Core utilization: WMMA 16×16×16 FP16 operations

Deep dive into the implementation:

The CUDNN kernel uses a sophisticated tiling strategy:

- Outer tile: 128×64 for the output matrix

- Inner tile: 64×64 for K^T×V multiplication

- Prefetching: Double-buffered shared memory loads

- Warp specialization: Different warps handle Q, K, V loading

Memory access pattern: The kernel implements a “stream-K” style parallelization where each thread block processes a slice of the sequence dimension, minimizing global memory traffic through careful reuse of Q and K matrices in shared memory.

Why it’s optimized: NVIDIA’s CUDNN engineers have access to internal GPU architecture details and can optimize for specific instruction scheduling, memory controller behavior, and even thermal characteristics that aren’t publicly documented.

Configuration 2: The Popular Choice

FlashAttention — Fast and Well-Known

1

2

3

4

5

torch.backends.cuda.sdp_kernel(

enable_flash=True,

enable_math=False,

enable_mem_efficient=False

)

What actually runs:

1

pytorch_flash::flash_fwd_kernel<Flash_fwd_kernel_traits<64, 128, 128, 4, false, false, cutlass::half_t>, ...>

Now we’re in familiar territory. This is the FlashAttention everyone talks about — the algorithm that made efficient attention possible for long sequences.

Performance Results:

- Execution time: 17.53μs per call (8% slower than CUDNN)

- Memory footprint: 49KB shared memory (49% of available)

- Grid config: [4, 2, 8] = 64 thread blocks (different parallelization strategy)

- Block config: [128, 1, 1] = 4 warps per block

- CUTLASS template:

Flash_fwd_kernel_traits<64, 128, 128, 4>

FlashAttention’s algorithmic innovation:

1

2

3

4

5

Tile dimensions breakdown:

- Br = 64 (sequence tile for queries)

- Bc = 128 (sequence tile for keys)

- d = 128 (head dimension - padded from 64)

- stages = 4 (pipeline depth)

Memory hierarchy optimization:

- Tiled computation: Processes attention in blocks to fit L2 cache

- Online softmax: Computes softmax incrementally without storing full attention matrix

- Recomputation in backward: Saves memory by recomputing attention weights during backprop

CUTLASS integration benefits:

- Efficient GEMM kernels: Leverages NVIDIA’s optimized matrix multiplication primitives

- Warp-level primitives: Uses

wmmainstructions for maximum Tensor Core utilization - Memory coalescing: Ensures optimal GDDR6 bandwidth utilization

Scaling characteristics: While only 8% slower at 512 tokens, FlashAttention’s O(N) memory complexity vs traditional O(N²) becomes dominant at longer sequences. At 4K tokens, traditional attention would require 64MB just for the attention matrix, while FlashAttention needs <1MB.

Configuration 3: Math Backend

Traditional Math-Based Attention

1

2

3

4

5

torch.backends.cuda.sdp_kernel(

enable_flash=False,

enable_math=True,

enable_mem_efficient=False

)

This is where things get interesting for all the wrong reasons. When you enable the “math” backend, PyTorch implements attention the textbook way: separate kernels for each operation.

Complete kernel execution breakdown (70 kernels total):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Step 1: Q⊗K^T (5 kernels, 335.55μs)

├─ ampere_sgemm_128x128_nn: 67.11μs avg

├─ Grid: [16, 4, 1], Blocks: [128, 4, 1]

└─ Tensor Core utilization: ~85%

Step 2: Scale + Softmax (25 kernels, 284.2μs)

├─ elementwise_kernel<128, 2>: 46.37μs avg (scaling)

├─ reduce_1d_kernel: 23.45μs avg (max reduction)

├─ softmax_warp_forward: 47.84μs avg (normalization)

└─ Memory bandwidth: ~420 GB/s achieved

Step 3: Attention⊗V (5 kernels, 233.85μs)

├─ ampere_sgemm_128x128_tn: 46.77μs avg

├─ Different memory layout than Step 1

└─ Tensor Core utilization: ~80%

Overhead: Kernel launches (40 kernels, ~677.54μs)

├─ CUDA context switches: ~15μs per launch

├─ Memory synchronization: ~2μs per kernel

└─ GPU pipeline bubbles: ~100μs total

Technical breakdown of the inefficiency:

- Memory traffic: Each intermediate result (512×512 attention matrix) requires:

- Write to GDDR6: 512KB

- Read from GDDR6: 512KB

- Total per head: 1MB × 8 heads = 8MB per sample

-

Kernel launch overhead: 70 kernel launches × 15μs = 1,050μs of pure overhead

-

Cache pollution: Intermediate results evict useful data from L2 cache

- GPU utilization: Individual kernels achieve 80-85% efficiency, but GPU sits idle during kernel transitions

Memory bandwidth analysis: While individual GEMM kernels achieve excellent bandwidth utilization (~650 GB/s), the overall pipeline achieves only ~120 GB/s due to fragmentation.

When to use it: Debugging, research, or when you need to understand exactly what each step is doing. Performance is not the goal here.

Configuration 4: The Memory Saver

When Every Byte Counts

1

2

3

4

5

torch.backends.cuda.sdp_kernel(

enable_flash=False,

enable_math=False,

enable_mem_efficient=True

)

What actually runs:

1

fmha_cutlassF_f16_aligned_64x64_rf_sm80(PyTorchMemEffAttention::AttentionKernel<...>)

This is the “memory-efficient” attention variant — designed for when you’re pushing the limits of your GPU’s memory.

Performance Results:

- Memory footprint: 19KB shared memory (19% of available)

- Grid config: [8, 8, 2] = 128 thread blocks (2x more parallelism)

- Block config: [32, 4, 1] = 4 warps, smaller blocks

- Memory efficiency: 87% less peak memory than traditional attention

xFormers memory-efficient architecture:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Tiling strategy:

├─ Query tiles: 64×64 (fits in 8KB shared memory)

├─ Key tiles: 64×64 (another 8KB)

├─ Value tiles: 64×64 (final 8KB)

└─ Working memory: <3KB for softmax computation

Total: 19KB vs 49KB (FlashAttention) vs 40KB (CUDNN)

Memory access pattern optimization:

- Smaller tiles: Reduced shared memory pressure allows higher occupancy

- Register file utilization: More computation in registers vs shared memory

- Global memory coalescing: 128-byte aligned reads for optimal GDDR6 efficiency

- L2 cache friendly: Smaller working set improves cache hit rates

Occupancy analysis:

- Theoretical occupancy: 100% (limited by register usage, not shared memory)

- Achieved occupancy: ~92% (measured via profiler)

- Warp efficiency: 96% (minimal divergence)

Why it’s slower despite better occupancy:

- More synchronization: Smaller tiles require more inter-warp coordination

- Reduced vectorization: 64-bit loads vs 128-bit loads in other implementations

- Increased arithmetic intensity: More computation per byte loaded

Memory scaling advantage: At sequence length N:

- Traditional: O(N²) memory for attention matrix

- Memory-efficient: O(N) memory with constant small factors

- Crossover point: ~1024 tokens where memory efficiency dominates

Performance vs. Purpose

Here’s how all four configurations stack up:

| Configuration | Execution Time | Speedup vs Math | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Disabled (CUDNN) | 16.26μs | 20.1x faster | Maximum performance, short sequences |

| FlashAttention | 17.53μs | 18.6x faster | Great all-around choice, long sequences |

| Memory Efficient | 29.58μs | 11.0x faster | Memory-constrained scenarios |

| Math-based | 1,631μs | 1.0x (baseline) | Debugging and research |

What This Means for Your Models

The takeaway isn’t just “use the fastest option.” Each configuration serves a different purpose:

For production transformer inference: Start with CUDNN fallback (all flags disabled). It’s the fastest for typical sequence lengths and has excellent hardware support.

For training large language models: FlashAttention becomes essential once your sequences get long enough that memory efficiency matters more than raw speed.

For pushing memory limits: The memory-efficient variant lets you trade some performance for the ability to fit larger batch sizes or longer sequences.

For understanding and debugging: The math-based approach shows you exactly what’s happening at each step, even if it’s painfully slow.

Reproducing This Analysis

The complete profiling setup used NVIDIA’s Nsight Systems profiler integrated with PyTorch’s profiler. The key insight was looking at the actual kernel names and execution times, not just high-level timing measurements.

Here’s the minimal setup to try this yourself:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

import torch

from torch.nn.functional import scaled_dot_product_attention

# Your test tensors

q = k = v = torch.randn(2, 8, 512, 64, device='cuda', dtype=torch.float16)

# Profile each configuration

with torch.backends.cuda.sdp_kernel(enable_flash=False, enable_math=False, enable_mem_efficient=False):

with torch.profiler.profile() as prof:

attention_output = scaled_dot_product_attention(q, k, v)

# Export and analyze the Chrome trace

prof.export_chrome_trace("trace.json")

The Bottom Line

Whether you’re optimizing inference latency, maximizing training throughput, or just trying to understand how attention actually works, knowing which kernel PyTorch chooses and why can make the difference between a model that crawls and one that flies.